Since the second half of the 20th century a long debate on corporate social responsibility has been taking place. In 1953, Bowen wrote the seminal book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. Since then, there has been a shift in terminology from the social responsibility of business to CSR. (Garriga & Melé, 2004, p. 51) He proposed that businesses establish a code of practices to reduce waste stemming from excessive profits and emphasized that companies must eliminate unfair business practices. (Khan, 2017, p. 4) Corporate social responsibility has been a known factor for many years, but because the definition of social is vague, it can mean anything to anybody (Frankental, 2001, p. 20). Corporate social responsibility is fundamentally grounded in ethical considerations, emphasizing businesses’ moral obligations beyond profit-making. In his well-known article in the New York Times, Milton Friedman (Friedman, 1970) states that a business’s social responsibility is to increase its profits, and similar like-minded scholars maintained that businesses’ primary goal should be maximizing profits. However, a rising body of research indicates that companies must embrace their ethical and moral duties in addition to financial rewards and legal compliance. As corporate social responsibility develops, businesses must use proactive management techniques to successfully incorporate CSR into their operations and secure long-term viability in a cutthroat industry.

Different social, economic, and ethical factors influence corporate social responsibility. While finding the starting point for CSR is not easy, its roots go back in history for many centuries. What is believed to be corporate responsibility has changed over time, from just philanthropy to the kind of responsibility where corporate social responsibility becomes the top priority, and more organized and focused planning instead of retroactive actions is the primary strategy. This was directly correlated to the broader paradigm shifts in markets, consumption, communication, and other ongoing societal challenges. Along with this, businesses can thrive and build a sustainable future only when they take note of the balance between economic, environmental, and social factors. Carroll’s article (Carroll, 1991, p. 39) proves that corporate social responsibility consists of multiple components and presents a structured approach to understanding them. By introducing the CSR pyramid, he demonstrates how businesses can balance their responsibilities to shareholders while addressing the legitimate claims of other stakeholders.

Early Theories of Corporate Social Responsibility

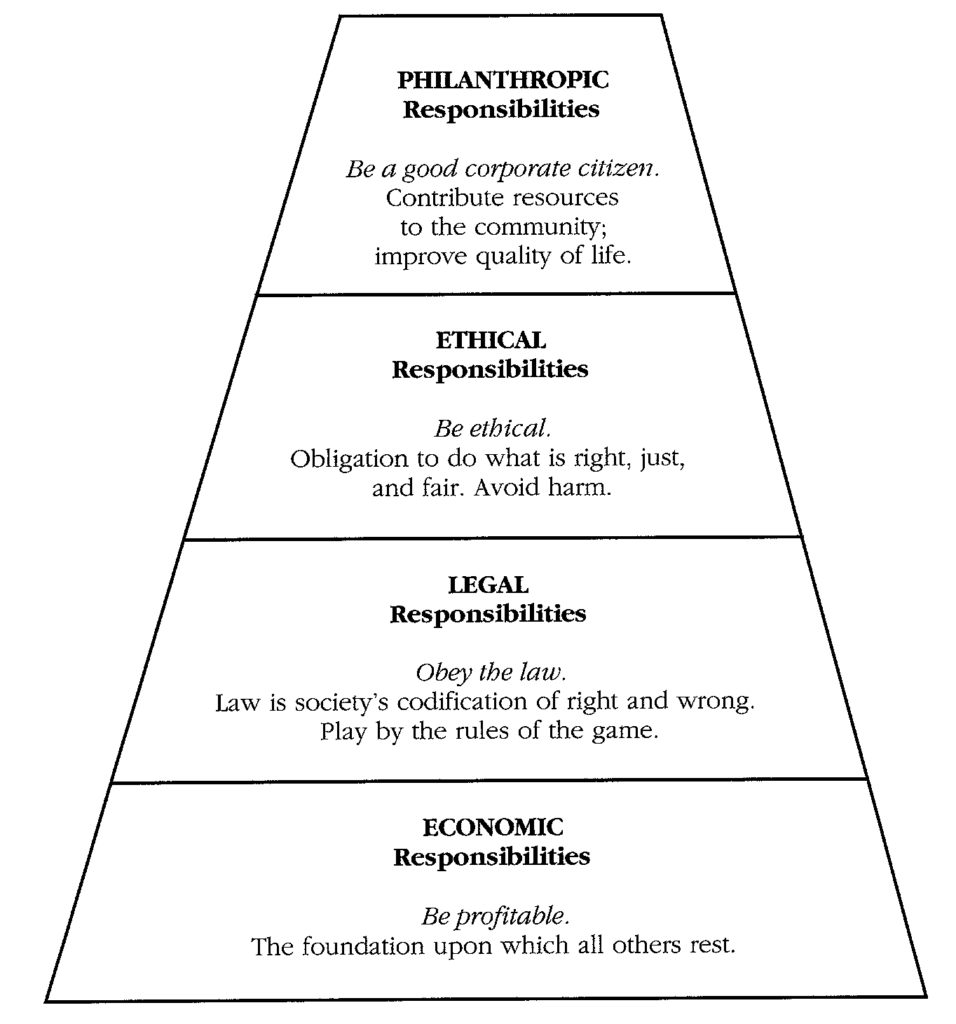

A pyramid developed by Carroll (1991), explains for CSR to be accepted by a conscientious business person, it should be framed in such a way that the entire range of business responsibilities are embraced. (p. 40) Furthermore, he mentioned four CSR factors economic, legal, ethical and discretionary social responsibility. (Coldwell, 2000, p. 49)

The pyramid represents Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility model (Carroll, 1991, p. 42), which categorizes a company’s responsibilities into four hierarchical levels. At the base, economic responsibilities emphasize the fundamental role of businesses in providing goods and services while ensuring profitability, as financial success supports all other responsibilities. Next, legal responsibilities require companies to comply with laws and regulations, ensuring fair and lawful operations. Moving up, ethical responsibilities encourage businesses to go beyond mere compliance, fostering fairness, justice, and positive societal impact. At the top, philanthropic responsibilities reflect voluntary contributions to society, such as charitable donations and community initiatives, promoting a company’s role as a good corporate citizen. This structured approach highlights the progressive nature of CSR, where businesses must first establish a strong economic and legal foundation before addressing ethical and philanthropic commitments.

Economic Responsibilities: Historically, business organizations were created as economic entities designed to provide goods and services to society, with the profit motive serving as the primary incentive for entrepreneurship. As the fundamental economic unit, a business’s principal role has been to meet consumer needs while ensuring acceptable profitability. Over time, this profit motive evolved into the enduring principle of maximizing earnings, reinforcing the importance of maintaining strong profitability, a competitive position, and high operational efficiency. A successful firm remains consistently profitable, as economic responsibility underpins all other corporate responsibilities. To achieve this, businesses must perform consistently with maximizing earnings per share, commit to being as profitable as possible, maintain a strong competitive position, and uphold high operating efficiency. Without financial sustainability, other obligations become secondary considerations. (Carroll, 1991, pp. 40, 41)

Legal Responsibilities: Society has sanctioned businesses to operate according to the profit motive and set clear expectations for them to comply with legal and regulatory frameworks established by federal, state, and local governments. As part of the social contract between business and society, firms are expected to pursue their economic objectives within the boundaries of the law. Legal responsibilities serve as codified ethics, embodying fundamental principles of fairness and accountability as defined by lawmakers. These responsibilities are not secondary to economic obligations but coexist as essential elements of the free enterprise system. To uphold these legal responsibilities, businesses must operate consistently with governmental expectations, comply with all relevant regulations, and act as law-abiding corporate citizens. A genuinely successful firm consistently fulfills its legal obligations and ensures that its goods and services meet or exceed minimal legal requirements. These principles illustrate the integral role of legal compliance in a responsible and sustainable business model. (Carroll, 1991, pp. 40, 41)

Ethical Responsibilities: Although economic and legal responsibilities incorporate ethical norms related to fairness and justice, ethical responsibilities extend beyond codified laws to encompass society’s expectations and moral standards. These responsibilities reflect what consumers, employees, shareholders, and the community regard as fair and just while protecting stakeholders’ moral rights. Ethical norms often precede legal mandates, acting as a catalyst for developing new laws and regulations, as seen in environmental protection, civil rights, and consumer advocacy movements. Ethical responsibilities also require businesses to embrace evolving societal values and expectations, even when they demand a higher standard of conduct than current legal requirements. However, these responsibilities are often fluid, subject to public debate, and difficult for businesses to navigate due to their lack of clear definition. The broader ethical principles derived from moral philosophy, including justice, rights, and utilitarianism, are superimposed on these expectations. The business ethics movement of the past decade has solidified ethical responsibility as a core component of Corporate Social Responsibility, continuously influencing and expanding legal obligations while setting higher moral expectations for businesses. (Carroll, 1991, p. 41)

Philanthropic Responsibilities: Philanthropy represents corporate actions that align with society’s expectation for businesses to be good corporate citizens, actively engaging in initiatives that promote human welfare and goodwill. This includes financial contributions, executive time dedicated to community service, and support for the arts, education, and other social causes. Unlike ethical responsibilities, which are inherently expected from businesses, philanthropic responsibilities are voluntary. At the same time, communities appreciate corporate contributions to humanitarian programs, and companies are not deemed unethical if they do not meet these expectations. This distinction highlights that Corporate Social Responsibility extends beyond philanthropy, as firms must first fulfill their economic, legal, and ethical obligations. While philanthropy is highly valued, it is often viewed as an additional layer of social responsibility—enhancing, rather than defining, a firm’s commitment to society. (Carroll, 1991, pp. 41, 42)

The CSR pyramid illustrates this hierarchy, beginning with economic responsibility as the foundation, followed by legal and ethical obligations, and culminating in philanthropic contributions that improve community well-being. In alignment with these principles, businesses should strive to operate by societal philanthropic expectations, support the fine and performing arts, encourage employee participation in charitable initiatives, assist educational institutions, and contribute to projects that enhance the quality of life, as reflected in Figure 1.

According to Carroll (Carroll, 1999, p. 289), the CSR firm should strive to make a profit, obey the law, be ethical, and be a good corporate citizen. Corporate social responsibility initially emerged as a strategy for corporations to build or protect their reputations beyond market operations (Crouch & Maclean, 2012, p. 1). Over time, CSR has evolved into a broader governance mechanism, with implications for corporate, economic, and even societal regulation, raising political and ethical questions about corporate influence in shaping regulatory frameworks.

Exploring Newer Research in Corporate Social Responsibility

Principles of the Social Responsibility

As Pulido (2018) explains, the principles of social responsibility establish a framework for organizations to guide their behavior and decision-making processes. These principles are interconnected and fall under two broad categories: stakeholder identification and behavioral regulation. Stakeholder identification involves recognizing the needs and expectations of those affected by the organization’s actions and establishing clear communication channels with them. This concept underpins the principles of accountability, transparency, and respect for stakeholder interests. On the other hand, behavioral regulation refers to adherence to legal, ethical, and international standards, ensuring a balanced approach across different levels of governance. This aspect is reflected in the principles of ethical behavior, respect for the rule of law, compliance with international norms, and commitment to human rights.

The first four principles focus on internal governance and stakeholder engagement. Accountability requires organizations to take responsibility for their impact on society, the economy, and the environment while remaining open to scrutiny. Transparency ensures that decisions, policies, and activities are disclosed in a clear and accessible manner, fostering trust with stakeholders. Ethical behavior involves adopting and upholding ethical values, developing governance structures that promote integrity, and implementing conflict resolution mechanisms. Respect for stakeholder interests emphasizes recognizing the rights, concerns, and perspectives of various stakeholders and addressing potential conflicts that arise from organizational decisions.

The remaining principles emphasize legal and ethical compliance on a broader scale. Respect for the rule of law requires organizations to be fully aware of and adhere to national, regional, and international laws, ensuring continuous legal updates and compliance measures. Respect for international norms of behavior becomes particularly relevant in cases where national laws are insufficient or conflicting, requiring organizations to uphold higher ethical standards. Finally, respect for human rights mandates that organizations recognize, promote, and safeguard human rights universally, even in contexts where local laws fail to do so. Collectively, these principles distinguish ISO 26000 from traditional quality management standards by providing a more explicit and comprehensive approach to social responsibility. (Pulido, 2018, pp. 131-134)

Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility

In a world where doing good is increasingly synonymous with doing well, CSR can be a win-win proposition for everyone involved. (Shribman, 2024) The companies make profits, and society benefits. Having identified social issues, Porter and Kramer (2006) make a bold claim: The essential test that should guide CSR is not whether a cause is worthy but whether it presents an opportunity to create shared value—that is, a meaningful benefit for society that is also valuable to the business. As a result, they show how a company can create a corporate social agenda, composed of strategic CSR. (p. 85) Unlike traditional philanthropic activities, strategic CSR aligns social initiatives with the firm’s business objectives, creating shared value for both the company and society. Strategic CSR moves beyond good corporate citizenship and mitigating harmful value chain impacts to mount a small number of initiatives whose social and business benefits are large and distinctive. (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 88)

As Porter and Kramer (2006) stated, “Strategic CSR moves beyond good corporate citizenship and mitigating harmful value chain impacts to mount a small number of initiatives whose social and business benefits are large and distinctive” (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 88). This means that rather than merely complying with external expectations or minimizing negative impacts, companies engaged in strategic CSR deliberately design initiatives that align with their core business objectives and contribute to long-term competitive advantage. Such an approach indicates that strategic CSR is inherently proactive, as it requires firms to anticipate and integrate social concerns into their strategic planning rather than reacting to stakeholder pressures.

Furthermore, “Strategic CSR involves both inside-out and outside-in dimensions working in tandem. It is here that the opportunities for shared value truly lie” (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 88). This dual perspective emphasizes that businesses not only influence society through their operations but are also shaped by external social conditions, reinforcing the idea that strategic CSR is an intentional and forward-looking strategy rather than a reactive measure. By leveraging both internal resources and external opportunities, companies can create initiatives that not only address social challenges but also strengthen their competitive position.

An example of this is Toyota’s response to environmental concerns: “Toyota’s Prius, the hybrid electric/gasoline vehicle, is the first in a series of innovative car models that have produced competitive advantage and environmental benefits” (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 88). The Prius demonstrates how strategic CSR can lead to innovation, providing both social and business value. This case highlights how strategic CSR is not just about mitigating harm but about creating long-term opportunities for differentiation and growth, positioning the company as a leader in both environmental responsibility and technological advancement.

Responsive Corporate Social Responsibility

Responsive CSR comprises two elements: acting as a good corporate citizen, attuned to the evolving social concerns of stakeholders, and mitigating existing or anticipated adverse effects from business activities. (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 86)

As Porter and Kramer (2006) stated, “Responsive CSR comprises two elements: acting as a good corporate citizen, attuned to the evolving social concerns of stakeholders, and mitigating existing or anticipated adverse effects from business activities” (p. 87). This suggests that responsive CSR is primarily reactive, as it focuses on addressing social concerns as they arise rather than integrating them into the company’s core business strategy. Companies engaged in responsive CSR often take action in response to stakeholder pressures, regulatory requirements, or reputational risks rather than proactively seeking to create shared value.

Additionally, Porter and Kramer highlight that “The best corporate citizenship initiatives involve far more than writing a check: They specify clear, measurable goals and track results over time” (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 87). This implies that while responsive CSR may go beyond simple philanthropy, it remains focused on stakeholder expectations rather than strategic business benefits. For instance, companies may engage in community engagement projects, sustainability reporting, or compliance measures to protect their reputation and maintain legitimacy rather than drive long-term competitive advantage.

A clear example of responsive CSR is General Electric’s initiative to support underperforming public high schools: “GE managers and employees take an active role by working with school administrators to assess needs and mentor or tutor students” (Porter & Kramer, 2006, p. 87). While this initiative undoubtedly provides social benefits, it remains peripheral to GE’s core business strategy, meaning its direct impact on the company’s competitive position is limited. This further supports the idea that responsive CSR is externally driven and primarily aims to satisfy stakeholder expectations rather than shape business innovation or long-term strategic advantage.

| Feature | Responsive CSR | Strategic CSR |

| Approach | Reactive | Proactive |

| Focus | Stakeholder concerns | Business-integrated social impact |

| Objective | Mitigate harm and ensure compliance | Create shared value and competitive advantage |

| Examples in REITs | Some charitable donations, sustainability reporting | Innovation in green technology, workforce development programs |

| Impact on Business | Limited strategic benefits | Enhances long-term business competitiveness |

Standards for Implementing and Assessing Corporate Social Responsibility

A number of international and local standards define guidelines for implementing and assessing CSR. Since SCR and sustainability have a deep connection, standards related to sustainability can also be considered. These include ISO 26000, which describes corporate social responsibility; ISO 14001, which concerns environmental management; the Global Reporting Initiative; and the United Nations Global Compact. These standards help implement and assess CSR in companies and industries.

ISO 26000:2010

The Standard is structured around four fundamental principles. First, it aims to contribute to sustainable development by addressing its three key pillars: economic, social, and environmental. Second, it emphasizes stakeholder engagement, ensuring that diverse perspectives are considered through open discussions and participation. Third, it underscores the importance of compliance with legal requirements while aligning with international norms of behavior. Finally, it advocates for full integration within the entire organization, embedding its principles into all operational levels.

The Standard is divided into seven chapters and two annexes. Chapter 1 outlines its aim and scope, while Chapter 2 defines key terms to clarify the understanding and application of social responsibility. Chapter 3 provides an overview of the factors that shaped the development of SR, tracing its origins and detailing its applicability across various organizations. Chapter 4 focuses on the core principles of SR. In contrast, Chapter 5 discusses two primary SR practices: First, how an organization recognizes and identifies its stakeholders, and Second, the interactions that occur between the organization, its stakeholders, and society. Chapter 6 defines the central SR topics and related issues, establishing links between principles, subjects, and action plans. Finally, Chapter 7 offers guidance on how to integrate SR into organizational structures. The annexes include a list of voluntary initiatives and tools for SR implementation, along with a compilation of abbreviations used in the Standard. A bibliography is also provided, citing relevant sources referenced in the norm. (Pulido, 2018, pp. 129-131)

ISO 14001

ISO 14001 is an internationally agreed standard that sets out the requirements for an environmental management system. It helps organizations improve their environmental performance through more efficient use of resources and reduction of waste, gaining a competitive advantage and the trust of stakeholders. (International Organization for Standardization, 2015, p. 2) ISO, the International Organization for Standardization, developed this business practice, which is helpful in the implementation of global environmental policies and in addressing industrial environmental issues more systematically and sustainably. ISO 14001 is not only a factor in the growing importance but also the requirement for organizations to display their dedication to environmental stewardship, the issue of sustainability, and increasing awareness of the environment globally, which have contributed to this importance. The most prominent standard in this family is ISO 14001 that provides requirements for an environmental management system. Organizations can achieve certification against the ISO 14001 standard, which means that a third party has verified their EMS’s conformity with the required ISO 14001 requirements. (Fabio Riillo, 2025, p. 1)

The recent change of ISO 14001:2015 involves some crucial additions that ultimately serve to boost a company’s environmental management performance. What is newly required is that management should blend environmental management systems into the broad strategic direction of the organization so that sustainability becomes an essential tactic of the decision-making procedure. Moreover, a more unambiguous definition of leadership commitment to environmental performance needs to be given, which means top management will be held more responsible for ensuring climate sustainability. The amendment indicates the importance of taking care of the environment; hence, sustainable resource use and climate change mitigation are among the mandatory proactive initiatives. Environmental consideration in every stage of the life cycle has been accomplished, emphasizing the fact that environmental issues need to be addressed in the development and in the end-of-life. Additionally, the author implements stakeholder-focused communication strategies to make the document more transparent. The revised format in the article is also to simplify integration with other management systems by accepting equal terminologies and definitions (International Organization for Standardization, 2015, p. 5).

Global Reporting Initiative

The GRI Standards enable any organization – large or small, private or public – to understand and report on their impacts on the economy, environment and people in a comparable and credible way, thereby increasing transparency on their contribution to sustainable development. In addition to companies, the Standards are highly relevant to many stakeholders – including investors, policymakers, capital markets, and civil society. (Global Reporting Initiative, 2021)

According to the Global Reporting Initiative website (Global Reporting Initiative, 2025), standards have been used by some 14,000 organizations in over 100 countries. The Standards are advancing the practice of sustainability reporting and enabling organizations and their stakeholders to take action that creates economic, environmental, and social benefits for everyone. As confirmed by 2024 research from KPMG, the GRI Standards remain the most widely used sustainability reporting standards globally.

United Nations Global Compact

The United Nations Global Compact is one of the most important corporate social responsibility initiatives. Its aim is to align companies’ strategies and operations with principles related to human rights, labor, the environment, and anti-corruption. (Orzes, et al., 2018, p. 633) As stated in The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact, “Corporate sustainability starts with a company’s value system and a principles-based approach to doing business. This means operating in ways that, at a minimum, meet fundamental responsibilities in the areas of human rights, labour, environment, and anti-corruption. Responsible businesses enact the same values and principles wherever they have a presence and know that good practices in one area do not offset harm in another. By incorporating the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact into strategies, policies, and procedures, and establishing a culture of integrity, companies are not only upholding their basic responsibilities to people and planet but also setting the stage for long-term success” (UN Global Compact, 2000) .

According to The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact (UN Global Compact, 2000), businesses are expected to uphold the following principles:

- Human Rights:

- Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights; and

- make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses

- Labour:

- Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

- the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour;

- the effective abolition of child labour; and

- the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

- Environment:

- Businesses should support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges;

- undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility; and

- encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies.

- Anti-Corruption:

- Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery.

References:

- Bell, M. & Taylor, B., 2024. How can investors balance short-term demands with long-term value?. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/insights/climate-change-sustainability-services/institutional-investor-survey

[Accessed 01 03 2025]. - Carroll, A. B., 1991. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), p. 39–48.

- Carroll, A. B., 1999. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38(3), pp. 268-295.

- Coldwell, D., 2000. Perceptions and expectations of corporate social responsibility: Theoretical issues and empirical findings. School of Economics and Management, University of Natal, Republic of South Africa, pp. 49-56.

- Crouch, C. & Maclean, C., 2012. The responsible corporation in a global economy. s.l.:Oxford University Press.

- Fabio Riillo, C. A., 2025. ISO 14001 and innovation: Environmental management system and signal. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume Volume 215.

- Frankental, P., 2001. Corporate social responsibility – a PR invention?. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, pp. 18 – 23.

- Friedman, M., 1970. A Friedman doctrine‐- The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html - Garriga, E. & Melé, D., 2004. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. Journal of Business Ethics, p. 51–71.

- Global Reporting Initiative, ., 2021. The global standards for sustainability impacts. [Online]

Available at: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/

[Accessed 4 March 2025]. - Global Reporting Initiative, 2025. About Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). [Online]

Available at: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/

[Accessed 03 March 2025]. - International Organization for Standardization, 2015. Introduction to ISO 14001:2015. Geneva: s.n.

- Khan, F., 2017. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’, A case of Orkuveita Reykjavíkur and its subsidiaries, s.l.: University of Iceland.

- Khenissi , M., Jahmane , A. & Hofaidhllaoui, M., 2022. Does the introduction of CSR criteria into CEO incentive pay reduce their earnings management? The case of companies listed in the SBF 120. Finance Research Letters, August.Volume 48.

- Orzes, G. et al., 2018. United Nations Global Compact: Literature review and theory-based research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, March , Volume 177, pp. 633-654.

- Porter , M. E. & Kramer, M. R., 2006. Strategy and society: the link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard business review, pp. 78-92.

- Pulido, M. P., 2018. Chapter 5 – ISO 26000:2010 Guidance on Social Responsibility: Concept and Practical Application. In: Ethics Management in Libraries and Other Information Services. s.l.:Elsevier, p. 127–168.

- Shribman, M., 2024. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Strategic Imperative For Modern Businesses. [Online]

Available at: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesbusinesscouncil/2024/10/11/corporate-social-responsibility-a-strategic-imperative-for-modern-businesses/

[Accessed 03 March 2025]. - UN Global Compact, 2000. The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. [Online]

Available at: https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles